Current migration trends in and within Europe

Migration is one of the most hotly debated topics in European politics. Developments since 2015 in particular have shown how complex and diverse migration to and within Europe can be, especially as situations vary significantly between countries. While immigration rates were on an upward trend for several years, the numbers dropped in March 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic reached Europe.

At the introduction of the New Pact on Migration and Asylum in September 2020, President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen emphasised that migration has always been part of the European story – and always will be (Von der Leyen 2020). It is important to remember that migration has been an influential factor in European politics and society for a long time, and not only since the refugee “crisis” of 2015/16. However, the rapid increase of migrant arrivals to Europe since 2015 has given the issue a new sense of urgency, while highlighting its complexity. Among other complicating factors, the unequal economic, social and political situations in European countries amplify the various challenges posed by migration (Filauro 2018, p. 6). This article introduces current trends in migration to and within Europe against the background of European social complexity, to which policy instruments such as the New Pact on Migration and Asylum seek to respond.

Migration to, within, and from Europe

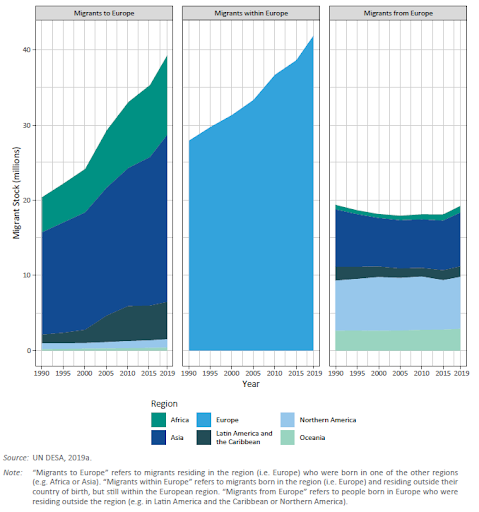

The World Migration Report 2020 summarises migration trends for Europe since 1990 (Figure 1) (International Organization for Migration 2019). Over 82 million international migrants lived in Europe in 2019, an increase of nearly 10% since 2015. Around 42 million of these international migrants were born in (and have migrated within) Europe, while around 40 million were born outside of Europe. From 2015 to 2019, the population of non-European migrants in Europe increased by about 3 million. Whereas migration to Europe and within Europe have both risen consistently between 1990 and 2019, the number of Europeans living outside Europe has trended downward, only increasing back to 1990 levels over the last few years. The most popular destination for European-born migrants in 2019 was Northern America with 7,4 million migrants from Europe (IOM 2020, p. 86-95).

Differences in European countries

As mentioned, there are significant economic, social, and political differences between EU-27 countries, which impact both net migration and the social reception of migrants. Eurostat provides a comparative overview of key indicators. In 2019, Germany, Spain and Italy were the top three countries of arrival by raw numbers. With 750,480 immigrants and 296,248 emigrants, Spain had the highest net immigration. Conversely, in countries such as Romania, Croatia, and Latvia, emigration predominates over immigration; skilled workers from these countries are particularly likely to migrate within Europe (Eurostat 2021a; ICF 2018).

Forced migration and asylum

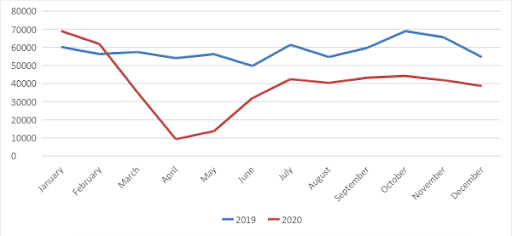

While the reasons for migration to and within Europe are multifaceted, the main focus of public discourse over the last few years has been forced migration to Europe due to crisis situations in non-European countries such as Syria. The European Commission’s Atlas of Migration 2020 provides an overview of key facts about migration drivers and residence decisions. Valid residence permits at the end of 2019 were mainly given for “Other” reasons, which include international protection (41%), “Family” reasons (38%), and “Work” reasons (17%) (European Commission 2019). Figure 2 shows the first time applications for asylum in 2019 and 2020. In 2019, 631,570 first-time applications for asylum were made – about 67,000 more than in 2018, but still not at the level of 2015 and 2016, in which more than a million applications were made. First-instance rejections have increased dramatically, from 38% in 2016 to 62% in 2019. Notably, the sociodemographic profile of asylum-seekers has also evolved: For instance, in 2016, 68% of new applicants were male, as compared to 62% in 2019 (Eurostat 2021b).

Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has severely impacted daily life worldwide, and in many countries it has motivated restrictions on internal and cross-border mobility. Accordingly, the pandemic has had a significant impact on migration (UNHCR 2020). Applications for asylum dropped significantly in March 2020, when the pandemic reached Europe and restrictions were implemented in most European countries. Since May 2020, the number of applications has increased again. However, it remains significantly lower than in 2019, perhaps due to insecurity regarding both conditions in Europe and the likelihood of making it across national borders. In 2020, there were 417,380 first-time applications – a decrease of 34% compared to 2019 (Eurostat 2021b). Experts anticipate that it will take some time for the number of applications to return to pre-2020 levels (Gamlen 2020).

From quantitative to qualitative research

The indicators summarised in this article are intended to deliver a baseline knowledge of recent migration trends, sufficient to understand the rationale behind certain European policy responses. More detailed statistics on migration to and from Europe, including country-specific data, subregional data, and migration data related to specific historic events, can be viewed online in the World Migration Report 2020, in the Atlas of Migration 2020, or by consulting the Eurostat webpage. However migration is a multifaceted subject, which cannot be understood on a quantitative level alone. For civil society and political decision-makers alike, it is critical to humanise migration by taking migrant’s own voices into account. The International Organization for Migration’s “I am a migrant” project (2017) and the European Commission’s European Migrant Advisory Board (2018) are examples of institutional efforts to amplify migrants’ voices – a goal toward which the qualitative research undertaken by projects such as PERCEPTIONS also aims.

Author: Ünal Furtana, Dr. James Edwards

References

European Commission. (2018). European Migrant Advisory Board (EMAB). Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/futurium/en/inclusion-migrants-and-refugees/european-migrant-advisory-board-emab.html (Accessed: 16 July 2021).

Eurostat (2021a). Immigration by age and sex. Available at : https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/migr_imm8/default/table (Accessed: 16 July 2021)

Eurostat (2021b). Asylum and first time asylum applicants by citizenship, age and sex – monthly data (rounded). Available at : https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/MIGR_ASYAPPCTZM__custom_1146657/default/table (Accessed: 16 July 2021)

Filauro, S. (2018). The EU-wide income distribution: inequality levels and decompositions. Available at: https://publications.europa.eu/resource/cellar/97058bfe-62f6-11e8-ab9c-01aa75ed71a1.0001.01/DOC_1 (Accessed: 16 July 2021)

Gamlen, A. (2020). Migration and mobility after the 2020 pandemic: The end of an age? Geneva: International Organization for Migration. Available at: https://publications.iom.int/fr/system/files/pdf/migration-_and-mobility.pdf (Accessed 16 July 2021).

ICF (2018). Study on the movement of skilled labour (Final report). Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=738&langId=en&pubId=8156&furtherPubs=yes

International Organization for Migration (2019). World Migration Report 2020. Geneva: International Organization for Migration. Available at: https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/wmr_2020.pdf (Accessed: 4 May 2021).

International Organization for Migration (2018). I am a migrant. Available at: https://iamamigrant.org/stories (Accessed: 4 May 2021).

Tarchi, D. et al. (2020). Atlas of Migration 2020. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available at: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/bitstream/JRC122942/aom_2020_online_final_v2.pdf (Accessed: 4 May 2021).

UN DESA (2019). International migrant stock 2019. Available at: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/data/estimates2/estimates19.asp

UNHCR (2020). Global Trends. Forced Displacement in 2019. Copenhagen: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Available at: https://www.unhcr.org/be/wp-content/uploads/sites/46/2020/07/Global-Trends-Report-2019.pdf (Accessed: 6 May 2021).

Von der Leyen, U. (2020). Press statement on the New Pact on Migration and Asylum. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/statement_20_1727 (Accessed: 16 July 2021)

Links

https://publications.europa.eu/resource/cellar/97058bfe-62f6-11e8-ab9c-01aa75ed71a1.0001.01/DOC_1

https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=738&langId=en&pubId=8156&furtherPubs=yes

https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/wmr_2020.pdf

https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/bitstream/JRC122942/aom_2020_online_final_v2.pdf

https://www.unhcr.org/be/wp-content/uploads/sites/46/2020/07/Global-Trends-Report-2019.pdf

https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/statement_20_1727

https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/MIGR_ASYAPPCTZM__custom_1146657/default/table

Keywords

Migration, Europe, COVID-19, Statistics