Involving and engaging stakeholders in perception studies

Mapping stakeholders, developing a stakeholder involvement roadmap and employing an engagement strategy are the three key components, which enabled the EU-funded project PERCEPTIONS to effectively include the major stakeholders in the area of migration in its activities. The project, which seeks to explore how narratives are formed and spread, as well as their impact on migration flows, successfully reached out to a broad circle of actors ranging from public institutions and first-line practitioners to the migrants themselves.

Mapping stakeholders

Stakeholders of a research project are generally entities and individuals that might be of interest for the project itself. Unlike the target groups, which consist of entities and individuals to whom the project is directly addressed, the stakeholders are a broader category, which includes all groups that can be of potential interest for research, investigation, elaboration, dissemination, etc.

The timely and systematic identification of stakeholders is essential not only for involving them in the project activities, but also for avoiding the risk of obtaining biased data, especially when a study is based on empirical research, fieldwork or social media analysis. Thus, as illustrated by previous experience, stakeholders should be identified, using pre-defined criteria and classified into groups on the basis of their professional and/or personal background. Furthermore, a geographical scope should also be defined to make sure that regional or country specific differences are duly taken into consideration.

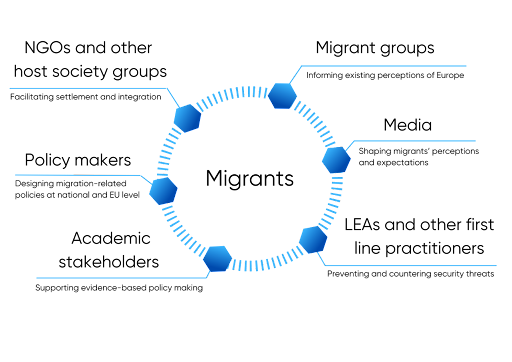

The PERCEPTIONS project classified the relevant groups of stakeholders in several categories: migrant groups, NGOs and other host society groups, policy makers, media, law enforcement authorities (LEAs) and other first line practitioners, and academic stakeholders. In terms of geographical scope, the project experts covered their own countries, but also included stakeholders from other countries, part of or outside the EU, especially neighbouring countries.

Evidently, migrant groups and media channels are the two main areas explored by the project. Therefore, the involvement of migrants and media professionals was key for the successful conduct of the research. Migrant groups were identified as the source to convey to the project team the impact of perceptions on migration flows and individual migration aspirations. Media channels, including in social media, came out as one of the main fields for studying the formation of perceptions by different narratives. These included conventional media (newspapers, TV channels and radio stations) with a regular and up-to-date web presence, online media outlets and specific social media groups and channels (Facebook pages, YouTube channels, blogs, etc.).

NGOs and other host society groups on the one hand, and policy makers on the other hand, were mapped in considerable detail, as those groups influence to a large extent the migration flows, the settlement and integration of migrants in the host countries. Both groups play a certain role in shaping countries’ migration policies and processes, as in many countries in addition to the settlement and integration efforts, led by institutions, there is a diverse range of activities and services provided by NGOs [1]. Besides, in some countries NGOs are also participating in the national consultative bodies on migration [2].

LEAs and other first-line practitioners are a vital part of the project’s stakeholder group. The threats generated by false and misleading narratives are materialised in their various lines of work, and especially in border and coastguard security. Some of these risks include inaccurate information leading to attempts to cross borders illegally or leave reception facilities, and unrealistic expectations leading to criminality, violent extremism and radicalisation [3]. Lastly, academic stakeholders are extremely important for spreading the project message and advising on the conceptual state of the art and implications of research action.

In the course of the work on the PERCEPTIONS project, a database of stakeholders was developed and systemised in a format that allows entries to be easily classified into categories and re-organised when necessary. To avoid data protection issues, the information was derived from public sources and, where necessary, the entries were anonymised.

The research team used various methods and sources for identifying stakeholders and collecting the necessary information about their field of expertise and contact details:

- review of websites of institutions and organisations;

- review of recent governmental and non-governmental projects and initiatives;

- ad hoc media monitoring to identify media outlets and journalists;

- review of researchers’ own contacts to point to relevant institutions, NGOs, scholars, policy makers and practitioners.

Within the first four months of the project, the stakeholder database accumulated more than 1,100 unique entries from 58 countries in the EU and beyond.

Involving stakeholders

Approaching stakeholders requires a flexible and tailored approach in order to achieve the highest possible impact. To do that, the PERCEPTIONS project team developed an involvement roadmap – a step-by-step practical plan on how to approach each group and encourage their participation.

The main factor to be considered when approaching migrant groups was whether they had a specific legal form of organisation (legal entity), or were just informal groups of people. This resulted in a multitude of communication exchanges between the project partners and those groups, which also varied in terms of formality of communication. Informal groups seemed to have a more fluid structure, and persons from such groups were rather contacted on an individual level.

NGOs and host society groups were contacted via a wide range of communication channels, with the degree of formality usually depending on the previous experience with these organisations or groups. Most often used channels included official letters, e-mail communication, phone calls, voice and non-voice communication via messaging applications, and personal meetings. When deciding which organisations to approach, proper account was taken of their publicly known written statements, opinions and studies. Stakeholders’ opinions were referenced in personal meetings. Policy makers, were mostly contacted via official channels consisting of official correspondence and/or formal meetings.

Media channels, despite the challenges related to their diverse format, proved responsive to less formal means of communication such as digital communication, phone calls and (informal) working meetings. Journalists and other media professionals, experienced in working on the topic of migration from the perspective of human rights and non-discrimination, seemed to offer more neutral, balanced and non-sensational overviews. At the same time, personal social media channels, although providing indispensable viewpoint and evidence about the impact of perceptions, were involved with extreme caution to ensure that their use for research purposes does not infringe upon their privacy rights.

LEAs and first-line practitioners were contacted via official or unofficial channels, depending on the level of their position (managerial or operative) and the extent, to which they had cooperated with the project partners before. Benefiting from the participation of LEAs as partners in the consortium, the research team utilised their expertise and professional networks to further expand the coverage of relevant professionals. At the same time, first-line practitioners should be and were selected to ensure maximum outreach to those who have first-hand experience with migrants and their perceptions about life in Europe.

Academic stakeholders were mainly contacted by their academic counterparts within the project consortium, via formal and informal channels depending on the level of familiarity and history of cooperation.

Finally, it is essential that rules on informed consent and personal data protection are always observed to make sure that the stakeholders’ involvement is a law compliant and data-protection-by-design-oriented process.

Engaging

Stakeholder involvement and engagement are, to some extent, overlapping concepts. Within the PERCEPTIONS project, involvement was used to mark the initial process of including a stakeholder within the project network, while engagement served to mark the achievement of the stakeholders’ sustained support to the project activities and uptake of results within and beyond the project cycle.

Engagement of stakeholders in the PERCEPTIONS project outlined several different strategies used either independently or in combination: inform (one-way communication), consult (gain information and feedback), involve (work directly throughout the process), collaborate (partner for the development of mutually agreed solutions), and empower (delegate decision-making on a particular issue). Depending on their level of interest and influence, stakeholders can be engaged through one or more of these strategies, e.g., informing is suitable for stakeholders of lower interest and influence, involving and consulting – for entities of lower interest, but higher influence, consulting – for entities of higher interest, but lower influence, etc.

Last but not least, an important tool for further expanding the impact of the PERCEPTIONS project and its results on both the scientific community and the relevant practitioners was the creation of a dedicated Expert & Advisory Board, which brought together prominent experts of various fields. The Expert & Advisory Board was established right at the beginning of the project based on a clear strategy of involvement activities for external experts representing a broad variety of actors and capable of delivering valuable inputs at different stages.

Note: This article is based on Stakeholder overview, involvement roadmap & engagement strategy

Authors: Dimitar Markov, Maria Doichinova

References

[1] European Commission, 2021. Governance of migrant integration across Europe [online country factsheets]. Available at: European Website on Integration.

[2] European Commission, 2021. Integration practices [online repository]. Available at: European Website on Integration.

[3] PERCEPTIONS Project, 2021. Migration to the EU. A Review of Narratives and Approaches [online]. Available at: PERCEPTIONS project website.

Keywords

stakeholders, identification, involvement, engagement, migration, perceptions